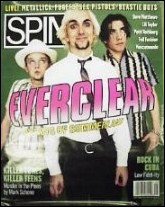

Art and Commerce

SPIN Magazine, August 1996

By Jonathan Gold

For someone who has straightened out his life and lived to write a hit album about it,

Everclear's Art Alexakis sure is loathed in his hometown. Is it well-deserved animosity, or just the hollow carping of jealous scenesters? Jonathan Gold examines the modern-rock evidence.

"Duuude... you're the guy who does that song!"

"Duuude... you're the guy who does that song!"

"I am?" asks Everclear's Art Alexakis.

"In that band, that band - what's your name again?"

"Art," says Art.

"No, man. I mean your real name."

"Art," says Art.

"Whatever, man. You're my hero!"

On a cool Friday night in May, Everclear is one of a dozen-plus bands passing through Pittsburgh's Riverplex, a muddy bit of flatland about five miles out of downtown, past the rusting steel mills, past the fragrant taverns; a few sodden acres with an amphitheater and a go-kart track.

Tonight's show, a modern-rock radio festival orphaned when the sponsoring station decided to go over to soft jazz, is subtitled "New Rock Revolt," and the Riverplex swarms with tie-dyed Hacky Sackers, clear skinned B-students, and the pale teenagers that populate alternative nation everywhere.

Nobody seems to be paying much attention to the Spin Doctors flailing Hobbit-like on-stage, not even the Spin Doctors themselves.

Everclear's bassist Craig Montoya and drummer Greg Eklund slouch in a makeshift dressing room whose cheaply paneled interior could pass for the set of those Calvin Klein kiddie-porn ads.

Everclear's trailer is a fairly popular hangout on the tour - there is always plenty of Heineken around, and Alexakis doesn't touch the stuff. Guys from Filter and the Nixons driftby to pay their respects, and drift out with green bottles wrapped in their fists.

Suddenly a member of Goldfinger bursts in, sweaty and out of breath, burbling about the wonders that a woman in leather pants had just performed on his person.

Eklund, lying facedown on a couch, pounds on a pillow in mock despair. "I need a girlfriend," he moans.

Montoya leans over and whispers in my ear. "That guy in Goldfinger already has a girlfriend," he says. "Some good boyfriend he must be."

The rituals of rock, whether it be classic or alternative, tend to be evergreen. At age 34, Art Alexakis - a recovering drug addict, the married father of a four-year-old girl - may be a little old for such a scene. On a swampy patch of riverband, a few yards from the stage, I find Alexakis staring out a small, unlit boat, its outline barely discernible in the dark, the faces of its passengers briefly illuminated by the faint swelling glow of a bong. We hear the sound of laughter across the black water, and the scent of marijuana is sharp even at a distance of 50 yards.

Alexakis used to know guys like that, guys who would risk getting creamed by a passing barge just to tie in on some good bud and hear some cool tunes for free. Alexakis used to be one of those guys. They probably know all the words to "Santa Monica," too - business is business.

"Paa-aarty," he shouts toward the boat.

"Woooo," the reply.

Alexakis might be just another Northwest rock auteur, one in a long line of goateed singer/songwriter/distorted-guitar dudes spreading gloom and detuned power chords across the land, but he has mastered more facets of his craft than just about anybody. He is a solid arranger, a competent video editor (he re-edited Kids director Larry Clark's video for "Heartspark Dollarsign" after Clark turned in a version deemed by Alexakis to be "virtually child pornography"), a skilled producer with a distinctive, stripped-down studio sound.

His lyrics - lush, heartfelt things that have one foot planted in drowsy teen nostalgia and the other in the vestibule of an outbound Greyhound bus - resonate in their simplicity. On "Santa Monica," and MTV fixture and a stone cold hit, he lights out for something like downsized version of Bruce Springsteen's "Promised Land": "With my big black boots and an old suitcase / I do believe I'll find myself a new place." Given the choice of loving something or leaving it, Alexakis, in his songs at least, usually opts to do both.

"When I try to get complex in my songs," Alexakis says, "I sound stupid. When I write about things that are simple, they come out fine. There's nothing wrong with anthems."

Onstage in Pittsburgh, Alexakis writhes low over the mike stand, arms churning power chords, voice hoarse and off-pitch but plangent somehow, cutting through the clouded torpor of the crowd's alt-rock ennui. The Hagfish shirt he wear rides up on his arms, exposing a sweaty Cat in the Hat tattoo. His lemon-colored mop, several inches longer than in any of Everclear's videos, wisps and clumps, shielding his eyes like a double handful of hay. Bassist Montoya, 25, the cute one in the band, cheetah-walks the stage like a wild-child metal guitarist, bobbing his skull as if to whip across his face the long hair he sheared off months ago. Eklund, 26, precise as a military percussionist, turns the approximate color of a scoop of peppermint ice cream as he coaxes an oversized sound from his floor toms.

Alexakis's face, striking in spite of its weak chin and wavy Greek nose, contorts into a grimace, and he spits out the chorus of "Heroin Girl" to the handful of moshers in the pit as the remaining throng waits patiently for the one Everclear song most of them know. He croons it, the band tight and clean, and even with a gazillion watts of amplification they are drowned out by the massed singing of the audience. They close with a rough through oddly unironic version of Tom Petty's "American Girl," another song Pittsburgh knows. Everyone is happy. Everclear are offstage less than a half-hour after they plugged in.

Forget Lollapalooza. Shine the shed tour. Stay home for the big reunion shows. The alternative-radio festival circuit - a dozen bands, a dozen DJ's and on to the next city - may be the purest expression of rock 'n' roll summer, a lo-cal ritual that doesn't pretend to be about anything but money, power, and an audience that can be bought and sold. Hang out in an airport in early summer and you'll see them all troop through: mid-level musicians slamming to the radio stations that keep their songs alive; minor legends praying for a fresh comeback hit; fledgling buzz bands hoping to nudge an MTV clip or two into an actual career. Sitting through an entire alternative-radio festival can be a little like watching six hours of trailers for movies you've already seen.

In a certain sense, it's preferable to catch one of your favorite alt-rockers in this denatured environ - you get all the hits without the drum solos, ballads, or acoustic jams. Twenty minutes is really as much as anybody needs to see of the Verve Pipe. But for the bands themselves, the radio circuit tends to be shallow, antithetical to their sense of art, less about music than about the stations' muscle. In the odd calculus of modern rock, No Doubt equals Gin Blossoms equals Garbage equals Everclear, all of the human experience flattened into three minutes, two chords, and free tickets for caller 94-point-seven when you hear "Santa Monica."

Art Alexakis, though, is nothing if not a businessman. He can discuss mechanical-royalty clauses with Talmudic subtlety. He regards SoundScan numbers with the devotion that Rotisserie-baseball geeks reserve for Albert Belle's slugging percentage, and he knows at any given instant where Everclear is placing on the Billboard Modern Rock and Top 200 charts. His conversation is peppered with terms like "adds," "sell-through," and "the kids." He is almost as big a fan of the contract Nirvana's lawyers negotiated with Geffen as he is Nevermind.

"I've always thought that people who get clean become very ambitious," Alexakis says. "I just did what it was clear I had to do: I became very driven. You've got to throw that obsessiveness into something."

"It throws people off sometimes," says Capitol A&R man Perry Watts-Russel, who signed Everclear to the label, " when they talk to Art and he sounds more like a manager than he does like a musician. But as long as he doesn't let the business interfere with the art, it's none of my business."

If Alexakis' crooked smile were not so familiar from Everclear's videos, if he was not wearing chipped sparkle nail polish and a wan green road tan, it would be possible, I think, to confuse him with the kind of 90's record-company executive who knows how to talk to Green Day as well as he does to the suits. When Alexakis says, as he often does, that his life's ambition is to be the president of a major label, you can believe him.

So although he enjoyed playing three sold out nights at the Roxy in L.A., though he's looking forward to headlining the "Summerland" tour with Tracy Bonham and Spacehog, radio festivals get the job done. He'd like to see his next single, a classic anger anthem called "You Make Me Feel Like A Whore," break out as a radio hit; he'd like to push the sales of Everclear's current album, Sparkle and Fade, from one million to two, three million and beyond. And Alexakis, at an age twice the mean of Buzz bin colleagues Silverchair, has little time to lose.

In a darkened hotel room in a Pittsburgh Holiday Inn, crashed out on his bed, Art Alexakis is compulsively sharing with me the details behind the breakup of his first marriage, the grisly nature of his late-teens fondness for reds, the OD death of his brother George, the OD death of a girlfriend, and a welfare-fraud charge he incurred up in Portland, Oregon. He hints at the sort of sex he had during the brief interregnum between the time his first marriage ended and the time he me this current wife, Jenny Dodson. "That's the great thing about pierced nipples," hesays. "You can never tell just which women have them." He inventories an argument with her upper arm badly bruised, and confesses the intolerable shame he felt when he noticed his little girl Anabella cowering in a corner, watching him hit her mother.

"Anabella was only 18 months old at the time," Alexakis says, "and she may not remember any of it, but that was the single lowest moment of my entire life."

Confession seems to be a compulsive behavior for Alexakis, the kind of ritual unburdening you sometimes see in former addicts. His story is well-rehearsed by now, worn with the telling: The youngest of five children, Arthur Paul Alexakis grew up lower-middle-class with his mom in the only housing projects in affluent West Los Angeles; lived in Roseburg, Oregon, with his sister; in Houston with his dad; and attended Santa Monica High School, where his classmates included Emilio Estevez and Sean Penn.

This is what Alexakis wants us to know about his childhood: He did drugs. He drank at age eight, smoked weed at nine, dropped acid at 11, and shot dope at 13, an age where most of his schoolmates were getting off on nothing stronger than Pop Rocks.

"Heroin wasn't really my thing," Alexakis says, tensing his lips into a rictus as if he were tasting the opiate's sting, "though I did get into speed-balls. Those were fun. You felt like you were going to split in two. But my favorite was shooting coke. Crank was much cheaper, but...you know. People called me a heroin addict, but I really wasn't: I liked coke, amphetamines, crystal. But I couldn't sleep sometimes, so I crashed with Nembutals, phenobarbitol, Seconal-rojas! We'd break into houses and steal drugs; that's when there were still things in people's medicine cabinets worth stealing. I kicked about four or five times, jonesed badly,and quit finally after I almost killed myself shooting up cocaine. I've been clean for 12 years."

Alexakis's musical history is less clear-cut than his stories of substance abuse, but when he talks about the music of L.A.'s golden age, he is more likely to reference skinny-tie new wave bands than he is the punks. He hints that he worked as a roadie, but refuses to say for whom. Alexakis at age 23, we may surmise, was drug-free, but a nerd.

In California, though, you get to keep reinventing yourself until you get it right. Come 1988, Alexakis was living in San Francisco, pounding guitar in a Big Black-style two-piece that never got around to playing a gig. The night his band broke up, he went out to a country-punk show with his first wife, and it must have been something of a revelation. The next day he bought a Telecaster and traded in his old Marshall for a reverb amp. Within a month, he was playing guitar in a goofy cowpunk band called the Easy Hoes, which toured some and eventually scored a minor college-radio hit, "The Gay Bar Song."

"I grew up," says Alexakis," listening to white-trash country: Merle Haggard, Dolly Parton, George Jones, Porter Wagoner, Hank Senior. I just loved that music."

Alexakis was working a day job at the time as production coordinator for a graphic arts company. A co-worker came one night to see him play, and, impressed, set Alexakis up with an indie label, Shindig. As Shindig's house producer, Alexakis documented the San Francisco cowpunk scene on the compilation LP Lazy, Loud, and Liquored Up. One of Shindig's releases was essentially an Alexakis solo record released under the group name Colorfinger, a country tinged thing that sounded a little like Everclear without the distortion pedals. But when Rough Trade and other major indie distributors went out of business a few years later, owing many thousands of dollars to tiny labels, Shindig settled for something like four cents on the dollar and was forced to shut its doors.

"I couldn't even get the record back," says Alexakis, "because they'd sold them all. My marriage broke up. My band broke up. My life was ruined. But in retrospect, if the label had been successful, I'd probably be sitting in an office right now. I probably wouldn't have bothered to start a band."

It was at a 1991 Colorfinger appearance in Portland that Alexakis met Jennifer Dodson, a pale, delicately beautiful record-store clerk. The two shacked up together back in San Francisco. Eight months later Dodson got pregnant, and the parents-to-be headed up Highway 101 to settle in Portland, where Dodson had her roots and Alexakis could escape most of his.

"We could just find a town / Make it what we want to be / No one really gives a fuck about us anyways" - from "Summerland."

There is a peculiar thing that happens to a man when he discovers he is about to father his first child. First there's elation, sure, then pride, but there's no escaping the prickly claustrophobia: Becoming a father is often the first permanent thing a man does in his life. Even - especially - if he's managed to maintain a semblance of adolescence into his 30's, even if his own father was absent, fatherhood marks the point where he forced to grow up, to provide.

Some men go out and find the day jobs they've resisted up to that point; a few slump into sort of a stunned, happy domesticity. Alexakis put an ad in the weekly Northwest music paper The Rocket: "Looking for bass player and drummer to form a band. Influences Pixies, Sonic Youth, X, Neil Young, Led Zeppelin." Everclear, with bassist Craig Montaya and original drummer Scott Cuthbert, had its first practice when Alexakis's daughter was just four days old.

"I was kind of overwhelmed by Art at first," says Montoya, nursing a Heineken. "I answered his ad and I had to hold the receiver away from my ear, he was so excited. He wanted to go on the road, he wanted to record an album, he wanted to go down to South by Southwest and the New Music Seminar and CMJ, and I was like, 'Wow, I've never been outside the Pacific Northwest.' He became my father figure at about the same time he became Annabella's."

Unbridled professional enthusiasm - often known in the pejorative as careerism - is not necessarily a quality that endears a budding rock star to a homegrown scene, especially one who drifts in from the big city thinking he knows how to do your music better than you do. Indeed, Alexakis is loathed by the Portland hipoisie, and he, in turn, loathes them right back. The cover line on a recent story in Portlands's local alternative paper, the Willamette Week, read: "Not so Everclear: Art Alexakis is the Hottest Rocker in Portland - and the Most Unpopular." When Everclear played Late Show With David Letterman later that week, a message taped to the back of Alexakis's sharkskin sport jacket read Most Unpopular. Dave didn't ask him to explain.

If Dave had, he might have heard the name Pete Krebs. Krebs is Everclear's worst enemy. This isn't a metaphorical sense - Krebs really is Everclear's worst enemy, a man convinced that Art Alexakis is the serpent who destroyed the Portland music scene, rock's beautiful Northwest Eden. Krebs in his late 20's is the singer for Hazel, one of the umptillion Portland bands signed by Sub Pop in the early 90's, and a fairly capable exponent of Northwest grunge himself. More to the point, perhaps, Krebs had a brief affair with Alexakis's now-wife Jenny Dodson right before Alexakis moved to Portland to be with her.

"I've been one of the most outspoken people about Everclear," says Krebs, "and through Hazel - talking to other bands on the road, doing interviews, educating audiences - I have lots of opportunities to tell people the truth about Art."

In 1991, the year Alexakis moved up from San Francisco, Portland was one of the first of a long line of rock scenes most likely to succeed, with a swelling population of disaffected college kids, a couple of great clubs, it very own edition of the Rocket, and a buzz, even from people in Seattle, that it might become the Next Seattle. Most of the popular Portland bands - the Spinanes, Pond, Sprinkler, Hazel, Crackerbash - were signed to important indies, and as with all the smallish, hottish Next Seattle of the country, from Chapel Hill to San Diego, the Portland scene closed ranks. Everclear was the last band anybody wanted to do well.

"Art came into town like a shark," says Krebs, "and nobody was prepared for him. He was one of the first people in Portland who knew what 'points' meant, who talked about records as 'units'. Art was no snot-faced nerd-boy talking shit at a club; he had obviously spent a lot of time thinking about where he wanted to be in five years."

In less than a year, Everclear went from playing small bars to drawing 1,000 people at Portland megaclub La Luna. A hastily recorded demo tape became an EP on Portland's Tim/Kerr label, then later the album World of Noise. Alexakis hired a pro to push it to college radio, and he mailed out the promo albums himself. And after Everclear signed to Capitol in June of '94, Portland saw an invasion of suits looking to ink... the next Everclear.

"Everclear built a following faster than any band I'd ever seen," says Tim/Kerr president Thor Lindsay, "largely because Art is the hardest-working guy in the business. What other local band is on the road 300 days a year? It's much easier to sit around in a coffeehouse and complain."

But it wasn't solely the band's precipitous rise that fueled the hatred of the Portland coolies. In December of 1993, Alexakis and Dodson quarreled (he'd been on the road; they'd both been fooling around on each other) and she threatened to take their daugher away. He socked her on the arm. She called the cops. He spent the night in jail, and went through 24 weeks of anger-management counseling. She was impressed enough by his improvement to go through counseling herself. They were married 16 months later.

"That counseling may have been the best thing that ever happened to me," says Alexakis. "I wish the experience that led to it hadn't happened, but...my dad hit my mom, my brother hit my sisters. It's in my family. I had to break the circle, that cycle of power and control, and I think that I have. Hitting a woman always seemed like the ultimate cowardly act, and I'm still ashamed."

If the Portland rock swells had been disdainful of Alexakis before the incident, they were positively contemptuous after news of it leaked out. Krebs took to lecturing people about domestic violence, using Alexakis as example number one. "Five out of six perpetrators of domestic assault continue to batter their wives," he says, a tad self-righteously. "Art could be the exception, the one in six, but the odds aren't good. I'm concerned for Jenny's safety; I'm worried she's in over her head. And I'm going to speak out."

"I can't believe I fucked that guy," moans Dodson. "This is worse than a veneral disease."

And harder to shake. After Alexakis mentioned his upcoming SPIN cover appearance on a Portland radio show, my voice-mail box started to fill with messages, and my fax machine vibrated with anonymously sent documents. I was sent multiple copies of a Willamette Week story by Richard Martin that blamed Alexakis for everything but the destruction of spotted owl habitat. Copies of legal documents, some sealed, pertaining to Alexakis's domestic-assault charge (the arrest report) rumbled through the fax too, and I received notes describing a welfare-fraud fine Alexakis had to pay last year. I returned calls from an anonymous guy who's sick of Alexakis' "confessional trip," and from a woman who thinks Alexakis should go back to L.A.

I reached Jennifer Dahl, who acted as Everclear's booker and den mother toward the beginning of the band's career, whose gripes mostly have to do with what she sees as insufficient gratitude for letting Alexakis use her credit card to get the band to the South by Southwest conference in 1993. "I wish somebody would drag up the real Art," Dahl says. "it would be fun to see him confronted with it."

"I spent a lot of time teaching guitar to 15-year-olds," says Krebs, "and they all love Everclear. Sometimes I think about explaining Art to them, why it's not right to like the band, but..."

"What happens," I ask," when they ask you to teach them 'Santa Monica'?"

There is a silence on the other end of the line. "They do ask," Krebs says. "But I just can't. I mean, it would be easy enough to learn the song and all, but..." An embarrassed cough fades off into a sigh." I ask them if it would be okay to teach them a Crackerbash song instead."

Unfortunately for Krebs et al., Alexakis isn't going anywhere soon. "Portland is my home now," Alexakis says later. "I live in a real neighborhood now. There are gays and lesbians, old hippies, environmentally conscious people, kids... I feel good about it. I want to run my neighborhood board, and I'm thinking of being on the board of my child's preschool. I'm here to stay."

It is a sunny day in Washington, D.C., on Saturday, and RFK Stadium blisters in pre-summer heat. The smoke of a dozen barbecue pits drifts into the stadium from the legion of concessionaires outside, and the crowd, 65,000 strong, stinks of suntan oil and Gatorade. HFStival is the grandfather of all modern-rock radio shows - it seems as if every frat dude on the Eastern seaboard has converged on this place, pressed khaki shorts and Rockports as far as the eye can see: no leather, no mohawks, no tattoos. No Doubt and the Pres of the USA play their hits; Cracker and the Gin Blossoms; the Foo Fighters and (until she's beaned by a frisbee) Jewel. Nobody looks at the stage - there are two giant video screens - and only a couple of dozen people dance.

But halfway through Everclear's set, there is an extraordinary sound, tens of thousands of voices singing "Santa Monica" along with Alexakis, softly echoing in the vast space, reminding me less of rock-concert ritual - if radio stations had these kinds of concerts 25 years ago, everybody would've sung along with "Smoking' in the Boys' Room," too - than of the sustained, hymn-like quality of say, a half-million Poles singing for freedom in a Gdansk shipyard. Alexakis may be all, some, or none of the evil things his detractors claim (need?) him to be, but one thing is for certain: Here, now, it could hardly matter less.

Drummer Eklund, who hasn't been in RFK Stadium since he played in marching band as a local teenager, is delirious, clearly living out a childhood dream. Even Alexakis, whom you'd think would be used to all of this by now, is stunned.

Backstage a few minutes after the set, still slick with sweat and a little out of breath, Alexakis almost gushes with pride. "'Santa Monica' has a real guitar sound, a melody, and the first time you hear the chorus is a little different than the third. In Florida, we saw a top 40 band play 'Santa Monica' and it was great. The crowd went nuts; everybody emptied onto the dance floor. I knew the song was a good song..." Alexakis mops his brow, and continues. "But you can never tell when a rock 'n' roll song is going to connect. This song, for some reason I'll never know, connects."